Treatment options for pancreatic cancer

Treatment options for pancreatic cancer

Treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the tumour and if it can be removed.

If your cancer is operable then the aim of treatment will be to cure the disease. If the cancer is more advanced, then treatment will focus on managing any symptoms and stopping the tumour growing or spreading.

Whatever the stage of your disease, your pancreas will have been damaged and may not be working effectively. You may experience problems digesting food and require Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy (PERT). This medication can replace any loss of function from your pancreas.

Alongside your treatment you may be interested in or hear about clinical trials. These are research studies designed to test a new medication or intervention that has not yet been licensed. The treatment offered in a clinical trial may be better, the same or worse than what you may have otherwise been offered. The positives and negatives of taking part in a clinical trial are discussed below.

Control the symptoms of pancreatic cancer

This booklet covers the different procedures used to control pancreatic cancer symptoms with practical information about your hospital visit and returning home. Includes a section about second opinions, clinical trials and questions to ask your doctor and a glossary to explain some of the terms used.

Read more

Treating pancreatic cancer

Treatments for pancreatic cancer vary and are dependent on the stage of the disease and fitness level of the patient.

These are some of the various treatment options available for pancreatic cancer.

Chemotherapy

-

Chemotherapy drugs for pancreatic cancer

The choice of chemotherapy you will be offered will depend on your tumour and your general health.

Names of chemotherapy drugs

Chemotherapy drugs usually have two names; a general name, but also may have one or more brand names. The general name is the chemical name of the drug, for example paracetamol. The brand name is the one given by the company/ manufacturer of the

drug for example Panadol®. Below the general names are stated first, in brackets are the brand names.The chemotherapy drugs sometimes used to treat pancreatic cancer are:

Gemcitabine (Gemzar®)

Used alone or sometimes in combination with another chemotherapy drug such as fluorouracil, capecitabine or nab-paclitaxel (see below) for advanced pancreatic cancer and after surgery to remove a tumour (adjuvant therapy).

Fluorouracil (5-FU)

Used alone and generally delivered as a prolonged infusion, often over days as an adjuvant therapy (after surgery) or as a sensitiser for chemo-radiotherapy (to make it more effective). It may also be given as a second line therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer not responding to treatment.

Capecitabine (Xeloda®)

An oral form (taken by tablet) of 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU). It is sometimes given along with gemcitabine (known as GemCap) or on its own as a radiotherapy sensitiser (to make it more effective).

FOLFIRINOX

This is a combination of 4 different agents (folinic acid [leucovorin], fluorouracil, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) and is used to treat advanced pancreatic cancer and occasionally before surgery to remove a tumour. It can cause more side effects than having individual chemotherapy drugs therefore is usually only given to very fit patients.

Nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane®)

Nab-paclitaxel has EU/UK approval for use in combination with gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer.

-

Chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer

Chemotherapy treatment is the use of cytotoxic (cell-killing) medicines to destroy cancer cells. However, the treatment reaches all of the cells in the body. Chemotherapy is therefore known as a systemic therapy. It is an important treatment option for many types of cancer.

Chemotherapy treatment is usually given over the course of weeks or months in cycles. These are rounds of treatment with breaks in between. You may have chemotherapy on its own or alongside other treatments such as radiotherapy or surgery. Usually you will be given chemotherapy by injection into a vein (intravenous). You may also be able to take certain types of chemotherapy as tablets or capsules by mouth (orally).

The majority of chemotherapies for pancreatic cancer are given as an out-patient, however this depends on the type of chemotherapy prescribed. It is sometimes possible to have chemotherapy at home. Your oncologist will discuss with you how and where you will have your chemotherapy and any possible side-effects.

-

Interactions with other medicines

Tell your doctors about any other medicines you are taking.

It is important to tell your doctors about any other prescription or over- the-counter medicines you are taking or will be taking, as these may affect how the chemotherapy works in your body. These include herbal remedies and antioxidant and nutritional supplements (such as vitamins and minerals) as well as pharmaceutical treatments.

-

Planning for chemotherapy

Your doctor should discuss all treatment options available to you when you are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Your medical team will recommend the best treatments for you but the decision about what treatment you would like is ultimately yours. When considering if chemotherapy is right for you, and what type of chemotherapy is best, your medical team will consider:

- The type of cancer you have

- Where in the body it is situated

- If it has spread

- Your general health

How often you have your treatment and how long it takes depends on the type of cancer you have, the type of chemotherapy, how well the disease responds to treatment and any side effects that you are experiencing.

You may need several courses of chemotherapy. Your oncologist will discuss this with you when explaining the treatment. The oncologist should make sure you understand the options available to you, the treatment you have chosen and that you understand what will happen next. This allows you to make the right decision for you and is called informed consent.

You will need blood tests before every chemotherapy treatment. This will make sure you have no infections and are fit to have treatment. It may be possible for you to have the blood taken at your GP’s surgery 2-3 days beforehand or at the hospital before your treatment begins.

-

Side effects of chemotherapy

hemotherapy is given because it kills cancer cells. However, chemotherapy can also damage other types of normal cells in your body.

People can often carry on with many of their day-to-day activities while having chemotherapy. But some drugs, due to the potential damage to normal cells, can have side effects.The side effects of chemotherapy will vary from person to person and will depend on the type of drug(s) you are taking. Your medical team will discuss potential side effects with you before your treatment starts.

General side effects can include:

- Vomiting and nausea (feeling sick)

- Diarrhoea

- Constipation

- Mouth ulcers

- Poor appetite

- Hair loss

- Redness and peeling on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (palmar-plantar syndrome)

- Nerve changes (e.g., pins & needles)

- Infertility (inability to have children)

Side effects are mostly temporary and often steps can be taken to prevent or reduce them. Speak to your medical team if you are concerned about any side effects you may be having.

Drop in blood cells

Many chemotherapy drugs will cause the number of blood cells produced by your bone

marrow to drop. This usually begins around seven days after you start each treatment

and can return to normal levels about three to four weeks after treatment. Your doctors

will be regularly checking your blood to monitor your blood cell counts while you are

having chemotherapy treatment.The drop in blood cells can lead to the following side effects:

- A drop in white blood cells (neutropenia) can lead to an increased risk of infection.

With fewer white blood cells, particularly your infection fighting neutrophil cells,

your body finds it harder to fight infections. Symptoms of infections can include

headaches, feeling shivery, having a cough or sore throat, achy muscles and a high

temperature (above 38°C). - A drop in red blood cells (anaemia) can leave you very tired and breathless.

Sometimes the levels drop so low that a blood transfusion may be necessary. - A drop in platelets (thrombocytopenia) can cause bruising and nosebleeds,

because platelets help the blood to clot. You may also find that your gums bleed

after you brush your teeth. Low platelet counts can also cause a rash consisting of

tiny red dots, called petechiae, or bruises on your arms and legs.

If you feel you have any of the above symptoms please discuss with your doctor and

they can suggest what will be suitable to help with these side effects.

Blood Clots

Cancer can make your blood more likely to form a clot (thrombosis) and having

chemotherapy also increases this risk. Blood clots can be very serious so it is important

to tell your doctor straight away if you have pain, redness and swelling in a leg, or

breathlessness and chest pain.However, most clots can usually be successfully treated with drugs to thin the blood. Speak to your doctor or nurse for more information.

-

Why is chemotherapy given?

Chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer can be given for several reasons:

- To prevent the cancer coming back after surgery or radiotherapy. The aim is to reduce the risk of the cancer coming back. This is called adjuvant therapy.

- To reduce the size of a cancer. Chemotherapy can be used to shrink the tumour in the pancreas before surgery, or radiotherapy can be considered. This is called neoadjuvant therapy. This is not yet routinely carried out in the UK.

- To shrink a cancer in order to control symptoms. In this case, chemotherapy can be given to try to prolong and improve quality of life.

- To increase the effectiveness of radiotherapy treatment.

Chemotherapy can be used alongside radiotherapy to increase the chance of treatment being effective. This combined approach is becoming more common and is known as chemo-radiotherapy.

-

Will chemotherapy affect my everyday life?

Chemotherapy affects people differently. You may feel unwell after each course of chemotherapy due to its side effects. This can last for days, weeks or months depending on the medication and your previous level of fitness. If you are having your chemotherapy in hospital you may need to adapt your usual routine. Let your medical team know if you have an event to attend or a holiday. It may be possible fit your treatment around this. Your oncologist will be able to tell you if this is possible.

Chemotherapy can come with side effects. You may experience these during your treatment and for some time after it. You may need to take some time off work or cut down on social activities during this time.

Chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer

This booklet describes how chemotherapy treatment works, how it is given and how it may affect the patient. Provides advice on coping with side effects. Includes a section about second opinions, clinical trials and questions to ask your doctor and a glossary to explain some of the terms used.

Read more

Surgery

-

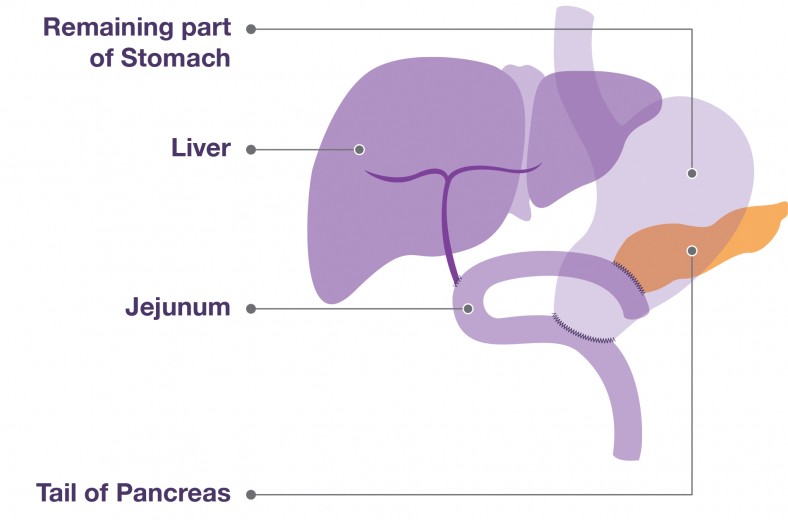

Distal pancreatectomy & splenectomy

A distal pancreatectomy is usually performed when a patient has a tumour in the body or tail (‘thin end’) of the pancreas.

This procedure involves having the tail (thin end) and body of your pancreas removed, leaving the head of the pancreas intact. Your surgeon will normally remove your spleen at the same time because it is located next to the tail of the pancreas.

Even though a distal pancreatectomy is less complicated than the Whipple’s procedure, it is still major surgery. The spleen is an important part of your immune system, and if it is removed, you will be on antibiotics for the rest of your life to prevent infections.

Some specialists may opt to perform distal pancreatectomies via a laparoscopic procedure. This is not common; it only happens in a few specialist centres and generally only when the tumour is small. As it is keyhole surgery, recovery time for patients is usually faster than for open surgery.

-

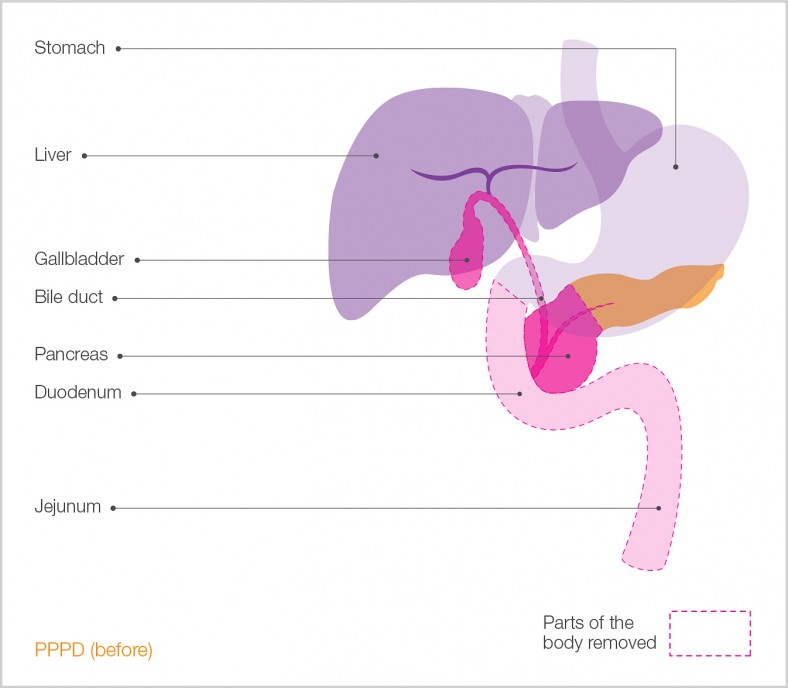

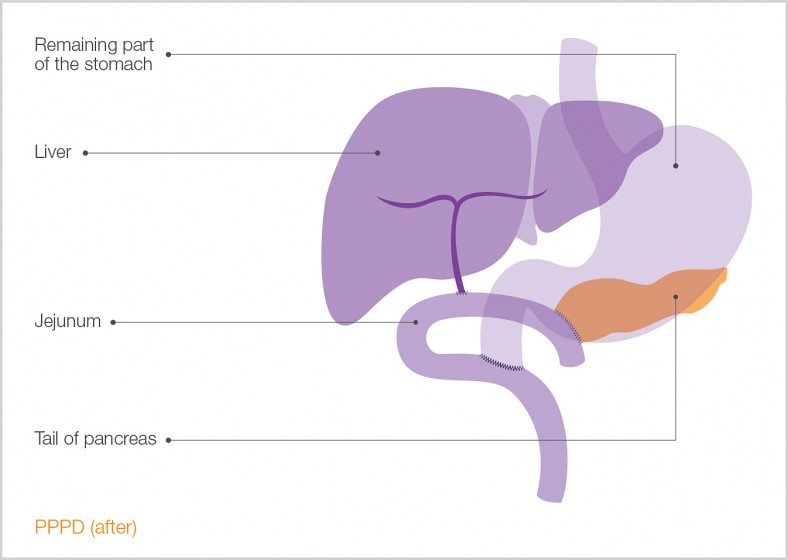

Pylorus preserving pancreatoduodectomy (PPPD)

The Pylorus Preserving Pancreatoduodectomy (PPPD) is a modified Whipple’s procedure. In this case, only part of the duodenum is removed and the pylorus (the part of the stomach that connects to the duodenum) is kept. Some doctors think this helps with food digestion after the operation.

There is no evidence however, that one of these operations works better then the other. It is often a technical decision, ask your surgeon if you have any questions about your operation.

Both the Whipple’s procedure and PPPD operations are major operations with risks of complications. You will need a general anaesthetic to keep you asleep during surgery and you’re likely to need around ten days recovering in hospital.

Before PPPD

After PPPD

-

Surgery for operable pancreatic cancer

If there is no sign that the tumour has spread beyond the pancreas and you are fit enough to undergo the operation, your doctors may decide to remove the tumour.

You will have undergone various tests such as ultrasound scans, CT scans and possibly had an endoscopy to determine that you have pancreatic cancer. These tests are important as they will inform the doctors about the size and position of the tumour and whether it is possible to have it removed (resected).

In order to have the tumour removed doctors need to know

- How big the tumour is: smaller tumours are easier to take out.

- Where the tumour is and that it doesn’t involve any major blood vessels or arteries.

- That there is not any cancer in surrounding lymph nodes or tissues.

- That the cancer has not spread to other parts of your body (such as the liver or lungs).

- You are fit enough to undergo a major operation.

Early-stage pancreatic cancer can be treated with the following surgical procedures:

-

Total pancreatectomy

A total pancreatectomy is a major surgery that involves the removal of the whole pancreas as well as your duodenum, part of the stomach, the gallbladder, part of your bile duct, the spleen, and many of the surrounding lymph nodes.

This operation is not often carried out as it has not been found to be any more effective for survival than either the Whipple’s procedure or the Pylorus Preserving Pancreatoduodenectomy (‘PPPD’) procedure.

There are some conditions for which it is used;

- When tumours are found in more than one location in the pancreas

- When the tumour extends along the pancreatic duct

- Sometimes when there is a rare or specific type of pancreatic tumour. This includes pre-cancerous IPMNs (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms). An IPMN is when abnormal growth of cells in ducts within the pancreas. As the abnormal cells grow they secrete a thick fluid called mucin leading to the formation of a cyst. Some IPMNs have a higher risk of developing into cancer e.g. those arising from the main pancreatic duct (main duct IPMN). However most IPMN’s are a type called branch IPMN’s which are often benign and able to be observed rather then actively treated.

- When it is extremely risky or impossible to join the pancreas either to the intestine or

stomach.

-

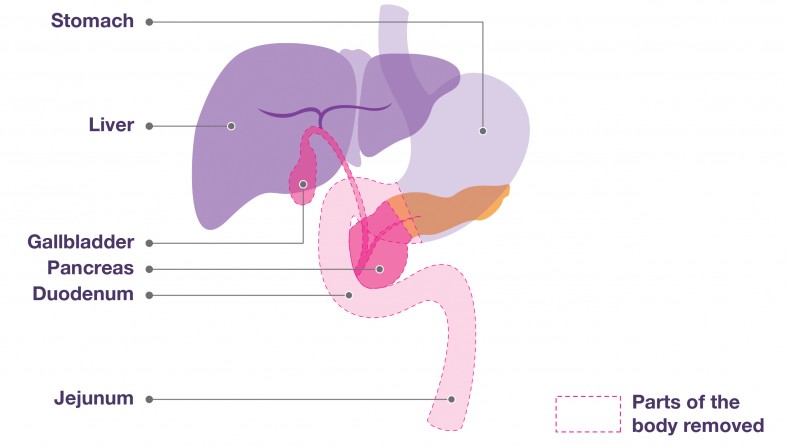

Whipple's Procedure and Pylorus Preserving Pancreatoduodectomy (PPPD)

Whipple’s procedure

The Whipple’s procedure (or pancreaticoduodenectomy, [‘PD’]) is the most common type of surgery to remove pancreatic tumours.The procedure involves removal of the “head” (wide part) of the pancreas next to the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). It is usually only carried out if the cancer has not spread beyond the head of the pancreas and patient is in good enough health to withstand a major operation.

What happens during a Whipple’s procedure operation?

The diagram (below) shows the stomach, liver, pancreas, gallbladder, small intestine and pancreas of a patient with a tumour in the head of the pancreas. The dotted lines show the area to be resected (cut out).

After PPPD

The head of the pancreas, a portion of the bile duct, the gallbladder and the duodenum (first part of the small intestine) are removed, along with part of the stomach. The rest of the pancreas, the bile duct and the stomach are reattached to the small intestine (see diagram below). This allows the pancreatic enzymes, bile and food to flow out into the gut, so that digestion can proceed normally. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed

Surgery for operable pancreatic cancer

This booklet contains information on the different types of surgery available and practical information about your hospital visit and returning home. It also includes a section about second opinions, clinical trials and questions to ask your doctor and a glossary to explain some of the terms used.

Read more

Radiotherapy

-

Radio Frequency Ablation radiotherapy

Radio Frequency Ablation (RFA) can be used to try to reduce the size of the tumour or relieve the symptoms of cancer (palliative treatment)

Radio Frequency Ablation (RFA) is not routinely used to treat pancreatic cancer and may only be available as part of a clinical trial.

How does it work?

RFA uses heat to destroy cancer cells. A probe is inserted into the tumour which delvers an electrical current. This electrical current heats up the cancer cells to very high temperatures which destroys them in a process known as ablation.

How is RFA given?

RFA can be given in a number of ways. The most common is either under local or general anaesthetic, probes are placed into the tumour and heated. The heat and current produce bubbles which remove and destroy the tumour cells. Doctors can track the progress of the therapy using an ultrasound or CT scan, so that they can see the results of the treatment in real time.

Sometimes you may have treatment another way, through the use of a laparoscope (small camera) or at the same time as surgery to treat the symptoms of pancreatic cancer such as a bypass.

How is treatment given?

Treatment will usually take place in an operating theatre or in the radiology department and can take between 1 to 3 hours depending on the size of the tumour being treated.

You will normally be asked not to eat anything for several hours beforehand and if you take any medicines, you will normally be asked to take these as normal. Should you be taking medicines to thin your blood such as warfarin or aspirin, you will told when you need to stop taking them.

Usually patients will need to stay in hospital overnight.

Are there any side effects?

Your medical team will explain any possible side effects and potential complications after treatment with RFA but sometimes patients may feel a little discomfort or pain for a few days afterwards which will be treated with painkillers.

It is also possible that you will feel unwell with a raised temperature and be tired for the first few days. This is a normal reaction and is caused by your body clearing away the cells that have been destroyed by this treatment. This should ease after about a week.

-

Stereotactic radiotherapy treatment

Some people can have sterotactic radiotheraoy as part of a clinical trial. This is where rays are fired at the tumour from a number of angles inside a radiotherapy machine. This is also know as sterotactic ablative radiotherapy or CyberKnife®

How does it differ to regular radiotherapy?

Like conventional radiotherapy, CyberKnife® delivers high doses of radiation to the tumour. The key difference is that many beams of lower doses are used at one time instead of just one large-dose beam. Each of the radiation beams carries a small dose of radiation and this allows a computer system to track the tumour’s position. It also respond to patients’ movements and breathing, ensuring only the tumour is targeted. This ensures that the tumour receives the high dose of radiation but surrounding normal tissue will receive significantly lower doses, making it safer for patients.

How do I get CyberKnife treatment?

If you wish to access CyberKnife® treatment you will need a referral from either your Consultant or your GP to one of the centres in the UK. Otherwise you find a suitable clinical trial in your area.

There are currently two private centres in London:

Current NHS Facilities include:

-

Radiotherapy for pancreatic cancer

Radiotherapy treats cancer by using high-energy x-rays to destroy cancer cells, while doing as little harm as possible to normal cells.

Radiotherapy is not used as often as chemotherapy or surgery to treat pancreatic cancer. You may have radiotherapy alongside chemotherapy or on its own. It works by using high energy rays to destroy cancer cells, whilst leaving your healthy cells as unharmed as possible.

Radiotherapy may be given:

- after surgery to try to reduce the chance of the cancer coming back (adjuvant). Both neo-adjuvant and adjuvant radiotherapy for cancer of the pancreas are still experimental treatments.

- in combination with chemotherapy to shrink the cancer and keep it under control for as long as possible (known as chemoradiation)

- to shrink the tumour and help to relieve symptoms such as pain, particularly if a bone is involved.

- as part of a clinical trial before surgery to try to shrink the cancer and make it easier to remove (neo-adjuvant).

All radiotherapy is targeted towards the tumour, but using complex computer models the focus of this targeting can be improved (stereotactic radiotherapy), allowing a higher dose to be administered with the same side effects in shorter time. “Cyberknife” is an example of this form of therapy. Whilst there are potential advantages from shorter treatment courses and perhaps fewer side effects, there is no evidence as yet that it is more effective than standard treatments.

Radiotherapy takes place in a radiotherapy department in a hospital. You may have a treatment daily Monday to Friday with a break over the weekend. Each treatment may take between ten and thirty minutes. A course of radiotherapy may take around six weeks.

Side effects and how to cope

The side effects of radiotherapy are related to the unwanted damage sustained by surrounding tissue. To minimise these unwanted effects, the total dose of radiation is split into up to 20 fractions given, for example, every weekday for 4 weeks. The dose of radiotherapy used to relieve symptoms such as bone pain is usually lower so you may have a shorter course of treatment and less chance of side effects.