UK scientists find way to ‘eliminate pancreatic cancer cells’ in just one week

Researchers at Cambridge University believe they have found a possible way to treat pancreatic cancer by using the body’s immune system to attack and kill cancer cells.

The scientists identified how the ‘wall’ around the tumour functions and, by using a drug in combination with an antibody to break down that protective barrier allowing cancer-attacking T-cells to get through to the tumour.

The findings, published in the journal PNAS (( Feig et al 2013Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti–PD-L1immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. PNAS vol 110 No.50 20212-20217 )) showed that initial tests in mice using the combined treatment saw a complete elimination of cancer cells in just one week.

Immunotherapy which works by stimulating the body’s immune system to attach cancer cells has shown promise in many cancers but so far, pancreatic cancer has not responded in the same way which may be due to the fact that pancreatic cancer forms a protective barrier around itself.

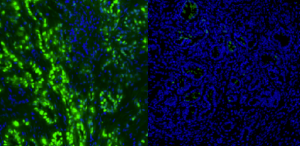

This research, led by Professor Douglas Fearon found that this protective barrier is created by a protein called CXCL12 that is produced by a specialised kind of connective tissue cell known as a carcinoma-associated fibroblast (or CAF). CXCL12 proteins coat the cancer cells forming a ‘protective shield’ that keeps the T-cells away. Using the drug AMD3100 known as Plerixafor (which enables T-cells to reach the cancer cells) along with anti-PD-L1, an immunotheraputic antibody (which enhanced the activiationof the T-cells) the scientists found that the number of cancer cells and the volume of tumour were greatly reduced. Amazingly they found that following combined treatment for one week, the residual tumour was composed only of premalignant cells and inflammatory cells.

While this work is of great interest, this now needs to be tested in humans. Clinical trials in humans are expected to begin soon at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.